If we are serious about rehabilitation in prisons, we must take reading seriously, not just as enrichment, but as a fundamental part of the system. Recently, Charlie Taylor published a thematic review of reading in prisons. The findings were clear; people in prison who can read have better outcomes and can engage with the regime more productively. This is a benefit not just to the individual, but to everyone living and working within the prison, and to wider society on their release.

Reading is a life skill. It increases opportunities for employment and training, builds connections with others and brings pleasure. For those in prison it’s also an escape, a way into another world, and another life.

It’s easy to see how helping someone learn to read opens a door to jobs and education, and then, hopefully, to a life away from crime. What the recent report makes especially clear is that reading also transforms life in the present. The inspectors found that learning to read, or increasing confidence with reading, can improve the quality of someone’s life while they are in prison, supporting wellbeing, safety and dignity in the here and now, not just in outcomes after release.

When someone finds reading difficult, written information, notices and instructions can be challenging, even impossible. Yet prison life relies heavily on the written word: forms must be completed to access healthcare, meals are ordered from written menus, legal correspondence arrives by post, and letters from friends and family may be the only connection to life outside. When people are excluded from these everyday interactions, or forced to rely on others for help, frustration, shame and withdrawal often follow. Power dynamics can emerge. Some people disengage altogether. Others may lash out or isolate themselves. Either way, confidence erodes and tensions rise.

The report’s findings underline this clearly. Of those who told the inspectors they need help with reading, 27% had spent one or more nights in the prison’s segregation unit in the six months before the inspectors’ visit, 34% had been restrained by staff, and 27% reported feeling unsafe. This compares to 10%, 13% and 14% of those who were confident with reading. Similarly, 18% of those needing reading support said they’d developed a drug or alcohol problem inside prison, compared to 6% of those who were comfortable reading. These are not marginal differences. They show that reading support is directly linked to safety, stability and wellbeing across the prison environment. Supporting one person to learn to read can have a ripple effect that benefits everyone who lives and works there.

Since 2022, all prisons in England and Wales should have a documented reading strategy. Last week’s report is a call to action to go beyond the document and make reading something that’s embedded, valued and recognised in each prison’s culture, at all levels. By including examples of good practice, the report also offers practical and achievable suggestions for change.

In his introductory remarks, Charlie Taylor notes how ‘even in the most challenging places’ some leaders have transformed the reading offer in their prisons. And in those which are outstanding, ‘leaders had promoted the importance of reading as an essential component of rehabilitation’. It is treated as a core component of rehabilitation, not an optional extra.

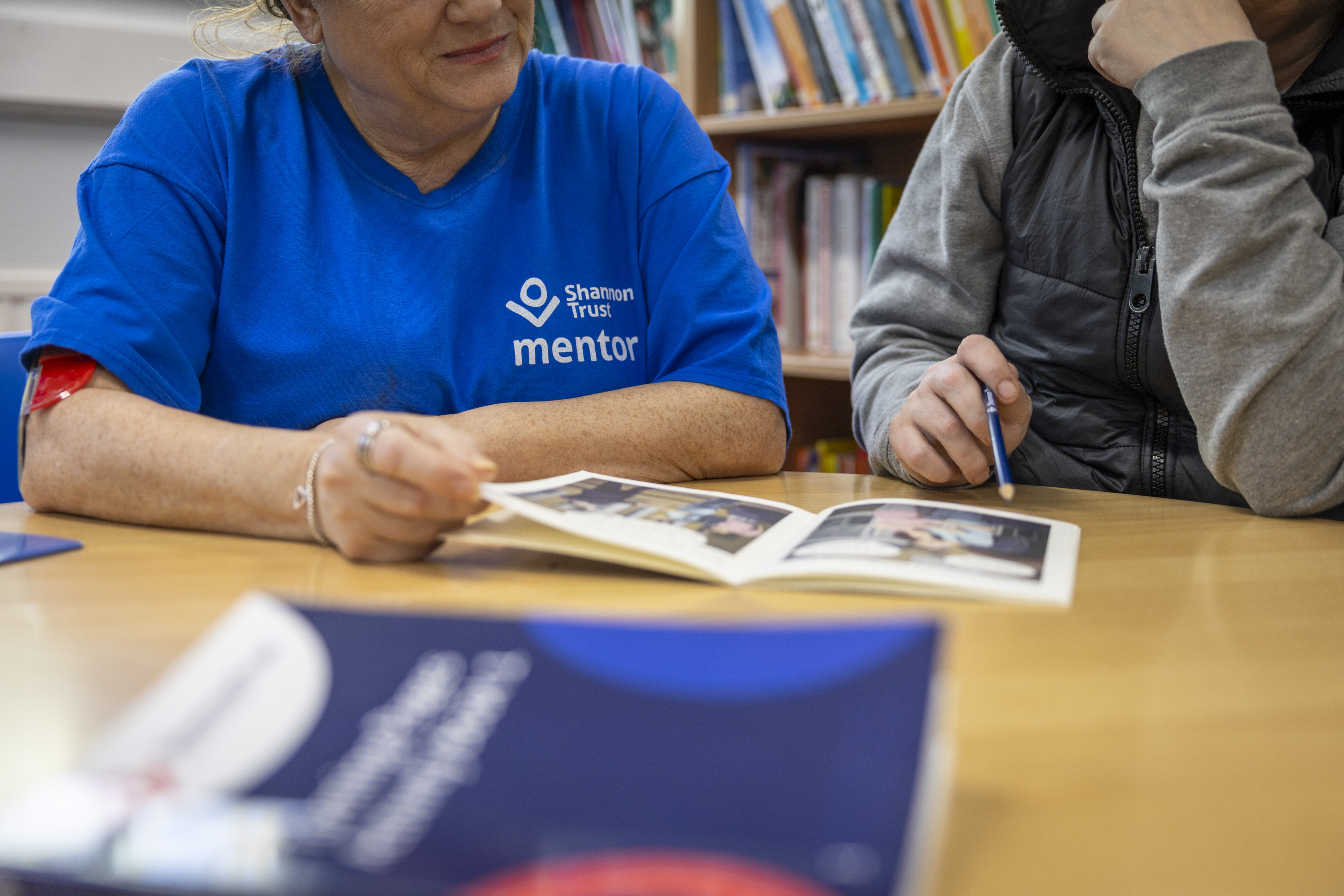

The report recognises what we at Shannon Trust see every day. Our peer-led reading programmes are a valued offer, delivered in partnership with prison education and library teams. Working one-to-one with a trained Shannon Trust peer mentor, learners build confidence at their own pace, in a space where mistakes are accepted and questions are welcomed. Libraries are often calm, safe environments for this work, and many learners tell us that gaining confidence through Shannon Trust is what enables them to move on to more formal education.

Our mentors are described as ‘well trained and supported’, and the report also notes the importance of Shannon Trust learning being 'distinct and separate from education and being prisoner-led’. This peer approach is a core strength of our model, and one that consistently delivers impact.

The report also highlights our role in prisons where there are no reading specialists within education teams, or where competing pressures mean reading is not prioritised. Even in these settings, Shannon Trust mentors continue to support learners. I’m pleased and encouraged that our value is recognised, and we stand ready to scale our contribution where strategies and leadership align.

I’m grateful to Charlie Taylor and his team for continuing to advocate for the transformative impact of reading. The Chief Inspector encourages a prison-wide reading culture, something that’s part of daily life for everyone, staff too. This includes having places for books that cover all abilities and interests, and widespread conversations about books, led from the top. The evidence is clear: Shannon Trust programmes work. We are ready to translate this proven impact into meaningful, system-wide change. The opportunity now is for prison leaders to engage with the findings, and partner with us to embed these effective approaches for the long-term.